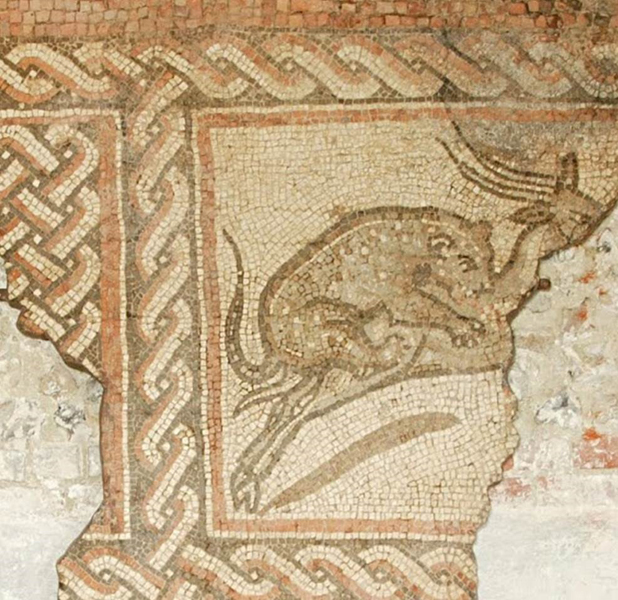

The mosaic would have been part of an elaborate pavement in the reception room of a luxurious villa and includes a depiction of a leopard pouncing on the back of an antelope as blood drips from its wounded prey.

Floor mosaics like this would have been chosen to reflect the values and beliefs of the villa’s owner and can help modern viewers understand the aspirations and education of country landowners who held power in the final decades of the Roman Era.

Apart from one smaller piece in the Dorchester Country Museum, much of the mosaic floor at the Dewlish Roman villa has now been destroyed, so this fragment is of crucial importance to understanding the whole composition.

This fragment has strong similarities to other fourth century mosaics found in the region surrounding Dorchester, ascribed to a Durnovarian School of mosaic workers. Although notable examples survived, including the Hinton St Mary mosaic in the British Museum, many of the mosaics assigned to the Durnovarain school have been reburied or destroyed.

This mosaic is a piece of history telling us about the lives of our Roman ancestors more than 2,000 years ago. It is an incredibly rare example of the Roman occupation of Britain and I hope that, even in these challenging times, a buyer can be found to keep this important and striking work in the UK.

The Minister’s decision follows the advice of the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA).

The committee noted that there were few mosaics from the Durnovarian school showing this quality and exceptional workmanship. It was also widely agreed that there was much to be learned about Romano-British mosaics from further research and study of the fragment.

The RCEWA made its recommendation on the grounds of the mosaic’s outstanding significance to the study of Romano-British art and history.

The mosaic‘s spirited depiction of a leopard bringing down an antelope is a brilliantly accomplished image of nature red in tooth and claw; the soaring leap of the deer, and the precise delineation of the leopard’s muscular power and ferocious grace is a tour de force of the mosaicist’s art. Such a resonant image, with its origins in the art and mythology of the classical world and beyond, has travelled a long way to Dorset, to feature in the villa of a wealthy Romano-British landowner; it must have been the latest thing in up-market house decoration. The grand mosaic from which this fragment came, dominating the principal public room of the villa, was clearly designed to impress the spectator with the learning and cultural aspirations of its owner. Perhaps this exotic symbol of the hunt, popular elsewhere in the Empire but exceptional in Britain, and its implicit theme of domination, were also intended to suggest its owner’s status and power.

In the later years of the Roman era in Britain, the representational innovation and technical sophistication of this mosaic, and of others produced by the Dorchester school of mosaicists, give fascinating insight into the lives of local Roman magnates, in a period seen as one of change and decline; they open up many questions and opportunities for investigation. For us to lose it from Britain would be a great misfortune.

Purchased at the Masterpiece Fair London from Edward Hurst Antiques for a client, export stopped and the money raised by the Dorset County Museum at the recommended price of £135,000 plus VAT.